|

RETRO/NECRO:

From Beyond the Grave of the Politics of Re-Enactment

Text / Pil and Galia Kollectiv

Art in the period of its dissolution, as a movement of negation in

pursuit of its own transcendence in a historical society where history

is not yet directly lived, is at once an art of change and a pure

expression of the impossibility of change.

—Guy Debord, Thesis 190, The Society of the Spectacle1

|

|

|

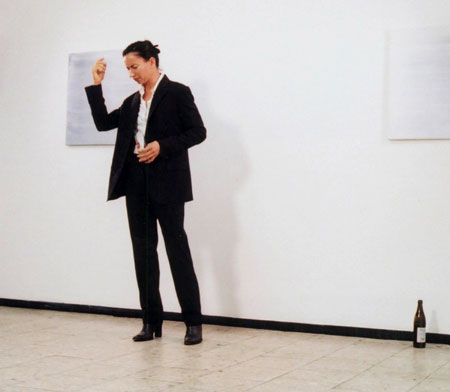

Jo Mitchell, Concerto for Voice and Machinery II, March 20. 2007, performance (courtesy of the artist and the Institute of Contemporary Art, London)

|

The industrial noise engulfing the theater is not unpleasant. The crowd

stands back cautiously at first, then moves closer to better observe

the action of the men and women on stage, unable to decide whether to

enjoy the music or keep at the safe distance normally assumed by

visitors to re-stylized period rooms in European castles. The sound of

a coordinated group assault on the humble wooden floor of the Institute

of Contemporary Art [ICA] is almost like a well-preserved archival item

stored on a CD of twentieth-century sound effects, next to the rattle

of a film projector and the gentle clang of an analogue telephone.

Originally used by Einstürzende Neubauten when they performed here in

1984, the handheld industrial machinery is in itself already a

nostalgic signifier of the might of European manufacturing power,

crumbling under the new forces of globalization and financialization.

More than twenty years on, we are at Jo Mitchell's 2007 re-enactment of

Concerto for Voice and Machinery,

commissioned by the ICA's Vivienne Gaskin, who has been responsible for

a significant number of artists' re-enactments. With actors recreating

the postures, sounds, and ensuing mayhem of the German industrial

band's destruction of the venue that commissioned them, this feels like

looking back at what is no longer there—like the light from a distant

ancient star that, collapsed thousands of years ago, is still visible

in our sky. Planted, rioters in the audience begin to rip apart the

stage, already in tatters from the air drills and saws, apparently

causing security to put a stop to the proceedings. But of course the

link between cause and effect has been broken: the ICA guards are

equally fake, and it becomes hard to tell when the performance is

actually over, the entire event having been meticulously predetermined

by fragmentary surviving documentation of the original show.

Guy Debord's thesis number 190 concisely defines the

paradox at the heart of twentieth-century art practices—the demand for

an impossible permanent revolution, the mediation of an unmediated,

authentic experience, and the constant pull of both past and future,

progress and decadence. The recent spate of artists' re-enactments of

historical events and performances seems caught up in this dialectic,

haunted by Debord's paralyzing circular discourse. In his writing about

history and time, Debord claims that modern time, in the wake of the

domination of linear history, is subordinated to pseudo-cycles of work

and leisure. Fads, consumerist seasons, remakes, and retro fashions

are, in his view, imposed by capitalism on history. Are we therefore to

see artistic re-enactments as logical conclusions of the spectacle's

repetitive imperative? Or do they, in fact, form blockages in the

spectacle's seamless flows, exposing the construction of time within

its media and technologies? On the one hand, re-enactment suggests a

reactionary nostalgia for an idealized past where unmediated, live

experiences were possible—a reference that reifies performance,

aligning it with the demands of the market for reproducibility. On the

other hand, opposing this self-defeating narrative, re-enactment is

celebrated as a means of interrupting the march of time as progress and

of rewriting canonical history against the forces of power and capital.

This opposition can ultimately be traced back to modern debates around

originality and reproduction, but the problem with both approaches is

that they quickly degenerate into a battle for art's purity in which

work is either denigrated for its complicity with capitalism or

burdened with the mission of somehow bringing it down.

|

|

|

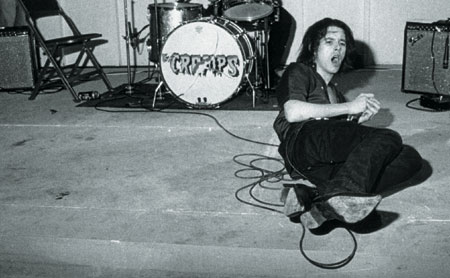

Andrea Fraser, (Kunst Muss Hängen) Art Must Hang,

2001, DVD, 32:55 minutes (courtesy of the artist, Friedrich Petzel

Gallery, New York, and Galerie Christian Nagel, Köln/Berlin) |

Much of the recent discussion around re-enactments has centered on

projects in which artists have revisited old, undocumented performance

work: their own-as with Marina Abramovic's recreation of Seven Easy Pieces at the Guggenheim Museum, New York, and Carolee Schneeman's restaging of Meat

Joy

at Whitechapel Gallery, London—or others'—as in Andrea Fraser's

re-enactment of a Kippenberger speech and the Synthetic Performances of

Eva and Franco Mattes, a.k.a. 0100101110101101.ORG, which are

re-enactments of Joseph Beuys' 7000 Oaks, Chris Burden's Shoot, and Vito Acconci's Seedbed

on Second Life. According to Peggy Phelan, who is oft quoted in

relation to the subject, performance art is defined by its

singularity—for in being repeated or reproduced it becomes something

different. A double resistance—to capital and the technology that

subjects performance to its dictates—signifies what she calls "the

ontology of performance."2

In fact, art's performative turn, which goes all the way back to action

painting and its emphasis on the singular action of the painter, has

been theorized as a displacement of the auratic object: "The artist

stepped (or danced) into the place of the object and rescued origin,

originality, and authenticity in the very unrepeatable and

unapproachable nature of his precise and human gesture-his solo act."3 Of course, as Philip Auslander writes in response to such claims, the liveness of performance can only ever be

conceptualized in relation to the possibility of recording:

the live and the mediatized exist in

a relation of mutual dependence and imbrication, not one of opposition.

The live is, in a sense, only the secondary effect of mediating

technologies. Prior to the advent of those technologies, e.g.

photography, telegraphy, phonography, there was no such thing as the

"live," for that category has meaning only in relation to an opposing

possibility. Ancient Greek theatre, for example, was not live because

there was no possibility of recording it.4

But it is precisely the tension between liveness and

mediation that seems to be attracting contemporary artists to classic

performances, salvaging from their meager documentation a script from

which to ask questions about authenticity and originality. As Mark

Cameron Boyd points out in his article, "Performance Simulacra:

Reenactment as (Re)Authoring," this logic can quickly lead to a dead

end:

It is this denial of the original, this re-casting of

previously enacted performances as "new experiences," that introduces

the final thorny summation of reenactments like Abramovic's as weak

copies, drained of their specific time-based authenticity, that

transform performance into vapid simulacra to re-place

the real Being of the original.5

|

|

|

Iain Forsyth + Jane Pollard, production still from File under Sacred Music, 2003, projection with sound, 22 minutes (courtesy of the artists and Kate MacGarry, London)

|

Despite these accusations of a weakened, slight return aiding the

commodification of the supposedly uncommodifiable, many attempts have

been made to valorize re-enactments as a critical practice, in

exhibitions like A Little Bit of History Repeated [Kunstwerke, Berlin; 2001],

Life, Once More [Witte de With, Rotterdam; 2004], Re- [Site Gallery, Sheffield; 2007] and most recently History Will Repeat Itself:

Strategies of Re-Enactment in Contemporary (Media) Art and Performance

[Hartware MedienKunstVerein (HMKV), Dortmund, and Kunstwerke, Berlin;

2007], in artists' projects—such as Jo Mitchell's and Iain Forsyth

& Jane Pollard's re-enactments of popular music concerts—and in a

series of debates, articles, and panel discussions, including the Art

And Re-Enactment Conference at The Australian National University in

Canberra. A question recurs in this context: on what grounds can we

differentiate critical—and therefore "good"—re-enactments from those

that simply rely on the familiarity of established art to launch new

careers or cash in on previously immaterial art? Or, as Melanie

Gilligan writes in her essay on performance and its appropriations,

"Which practices involving re-enactments might be retrograde

withdrawals from new aesthetic and political struggles, and which

others are catalysts for them?"6

|

|

|

Jeremy Deller, stills from The Battle of Orgreave, DVD, 2001, 62:37 minutes (directed by Mike Figgis; commissioned and produced by Artangel, London; photo: Martin Jenkinson)

|

Against the Debordian pseudo-cyclical time produced by trite Hollywood

remakes, Sven Lütticken suggests that art might be better able to

tackle reiteration as a form of critique: Perhaps the peculiar economy of the art world makes it a

more suitable sphere for the realization of remakes that resist the

dominant culture of repetition. But wherever it originates, the hope

held out by the remake lies in the liberation of the dormant

possibilities of mass culture—its utopian potential. The vicious circle

of standardized remake production—its frozen movement of mythical

signs&mash;needs to be derailed. It is intrinsic to these signs

that such a practice is possible. The myths of the media themselves

harbour a potential to generate second-degree myths that offer glimpses

of what Barthes called a "true mythology," in which myth is fleetingly

transformed by reason and history.7

|

|

|

Iain Forsyth + Jane Pollard, production still from File under Sacred Music, 2003, projection with sound, 22 minutes (courtesy of the artists and Kate MacGarry, London)

|

The desire to liberate mass culture's utopian potential seems to lie at

the heart of many artistic re-enactments. Jo Mitchell was hoping that

the re-enactment of Concerto might "create a rupture in our

viewing and witnessing in relationship to the idea of the authentic

experience and in this sense challenge what might be seen as an

apathetic consumption of experiences." The need to reexamine and

question passive consumption of ideas and historical narratives unites

many re-enactment projects. Jeremy Deller's The Battle of Orgreave,

2001, one of the progenitors of this strategy, famously revisited the

miners' conflict with Thatcher's police forces with the intention of

reinserting the miners' perspective, originally vilified in the press,

into history. Iain Forsyth & Jane Pollard, who have produced

several re-enactments including the last performance of David Bowie as

Ziggy Stardust and the Cramps' gig at the Napa asylum, have claimed

that it is the gap between the reproduction and its point of origin

that cuts through the mediation to reveal the real and subvert the

logic of the spectacle: it's rarely the event or action being repeated that we're

interested in reconsidering. Repetition works like a catalyst, and it's

our relationship to the imitation and the act of creating and

witnessing the "copy" where something interesting happens. Failure is

hugely important to us, and understanding its importance is vital to

our work. Copying anything, the copy never reproduces the original

completely. And this shortfall is where the real emerges, where

understanding can begin. Good art always, at some level, fails.8

|

|

|

Irena Botea, stills from Auditions for a Revolution,

2006, video installation, mini-DV and 16mm film on mini-DV, transferred

to DVD, 22 minutes, English and Romanian (courtesy of the artist) |

At Dortmund's HMKV, as part of the exhibition History Will Repeat Itself: Strategies of Re-Enactment in Contemporary (Media) Art and Performance,

Forsyth & Pollard's File Under Sacred Music,

2003, a video of contemporary musicians performing as the Cramps to a

mentally disabled audience replicating the bizarre occasion at the Napa

Mental Institute in California, shares a noisy space with Deller's film

and a host of other—mainly video—works looping repetitions of

historical instances and commentaries on the appropriation of the past.

American students rehearse a revolution that has already been

televised, reading out transcripts in a language they do not speak

alongside original footage from Romania, 1989, in Irina Botea's Auditions for a Revolution, 2006. Felix Gmelin's Farbtest, Die Rote Fahne II, 2002, reconstructs Gerd Conradt's film Farbtest, Die Rote Fahne,

1968, of a relay run of young men carrying a red flag through Berlin,

in which his father participated, this time transposed to a far less

radicalized Stockholm.

|

|

|

Felix Gmelin, stills from Farbtest, Die Rote Fahne II,

2002, 2-channel video installation, 12 minutes, silent (courtesy of the

artist, Maccarone Inc., New York, and Milliken, Stockholm; producers:

Felix Gmelin, Anna Sohlman, and Hinden/LännaAteljéerna AB; photo:

Tobias Sjödin)

|

In The Eternal Frame,

1975, T. R. Uthco & Ant Farm refilm Kennedy's assassination, this

time with the president's full awareness of his status as a media

image. The selections avoid the obvious Abramovic/Acconci/Schneeman

references in favor of a wider exploration of the subject. Curator Inke

Arns explains:

We decided not to include artists performing or re-enacting

performances from the 70s for example. This has been done in shows

quite a few times already and content-wise we wanted to concentrate on

artists repeating historical events. It was about how we relate to

history and how it is conveyed or mediated to us. The question of media

is very important. We are moving forward in time and, depending on our

position in time, history becomes readable in a different way. In the

last five or ten years, there has been a growing interest in the

strategy or logic of re-enactment, which means taking things out of

history books and making them happen again to allow for a different

kind of experience that is neither reading nor looking at images. It

has to do with the fact that, in a media-saturated society, you are

more and more unable to relate to what's been going on.9

|

|

|

Rod Dickinson + Tom McCarthy, Film

Still: Greenwich Observatory, approx 4pm, Feb 15th, 1894 and Martial

Bourdin depicted in The Sun, Saturday Feb 17th, 1894 from Greenwich

Degree Zero, 2006, installation, including film footage

(reconstruction: Royal Observatory, Greenwich Park, London), 15 tables,

15 lamps, 30 chairs, archival materials, photographs, video (courtesy

of the artist) |

There is a danger in this reading of re-enactments as engines of

criticality, which deals mostly with questions of commodification (of

art practices and historical moments), or of spectacle and simulation,

and ultimately relies on the very categories that are used to condemn

supposedly facile remakes. We run the risk of reducing re-enactments to

a list of collaborators and resistors of capitalism and its

institutions: artists either produce passive spectators obeying the

pseudo-cyclical logic of the market or emancipate their viewers from

the hold of the media and its narratives by short-circuiting its fake

cycles. Whether we single out unrealized utopian moments and rewrite

them as successes—as in Rod Dickinson and Tom McCarthy's Greenwich Degree Zero,

2006, a re-enactment of the failed bomb attack on Greenwich

Observatory, also on view at HMKV—or failures—as in Forsyth &

Pollard's flawed reconstructions of mythical performances, we could

find ourselves forever stuck within Debord's "art of change and a pure

expression of the impossibility of change." However, as Jacques

Rancière has maintained, this is only because, in insisting on this

relationship between performance and politics, we are making

contradictory demands:

the equivalence of theater and community, of seeing and passivity, of

externality and separation, of mediation and simulacrum; the opposition

of collective and individual, image and living reality, activity and

passivity, self-possession and alienationŠmakes for a rather tricky

dramaturgy of guilt and redemption. Theater is charged with making

spectators passive in opposition to its very essence, which allegedly

consists in the self-activity of the community. As a consequence, it

sets itself the task of reversing its own effect and compensating for

its own guilt by giving back to the spectators their self-consciousness

or self-activity.10

When we renounce this idea that there is a truth and a corresponding

politics to be uncovered once the spell of the spectacle is broken,

subtler distinctions in terms of the temporal play involved in

re-enactments come to the fore. Following Nietzsche's "Untimely

Meditations," Michel Foucault opposes history and genealogy: unlike the

supposed scientific objectivity of history, which seeks to trace the

inscription of a "point of origin" which "comes before the body, before

the world and time"11 on the present, genealogy is

concerned not with the birth, but with the emergence of regimes of

knowledge. Rejecting the notion of origin of historical moments,

Foucault's genealogy privileges the accidents, the coincidences, and

the ironies that inscribe time with meaning. Within this framework, a

historical moment is never new, which means that there is no original

to repeat. A successful re-enactment would therefore simply expose this

historical moment to a whole new set of "haphazard conflicts" that

ultimately produce a "true historical sense [that] confirms our

existence among countless lost events, without a landmark or a point of

reference."12

This disloyalty to the point of origin does not amount to historical

relativism, but rather activates history from within the present,

allowing us to move away from the sterile attempt to cut through the

infinite mediations of the spectacle. This is also where, as Inke Arns

observes, artistic re-enactments diverge from historical re-enactments

of famous battles:

If you see the show in the context of popular re-enactments (as in

medieval villages or civil war battles), the artists here deal with

real history that has to do with life today. The pieces in the show,

despite dealing with historical events, are never nostalgic because,

unlike popular re-enactments that don't make a connection to yourself

and your time, the works here deal with twentieth-century events and

make a very direct connection to your role in them.

For Rod Dickinson,

the specific historical point of origin of these works is

important, but primarily because it can offer a play of interpretation

and create a discourse around the idea of historical representation.

Perhaps this is rather different from a more relativist approach where

the point of origin might not be seen as important as the

interpretation. The audience is presented with something inherently

contradictory in that they are being presented with something live and

happening in real time, yet they know that this is an impossible

scenario, since the event has already happened, and they know the

outcome (in most of my events/work the audience is given information

sheets that tell them what happened). Their "live" experience is

constantly undermined by knowledge about what they are watching (or

participating in), which is prescribed and is being carefully re-staged.13

|

|

|

Walter Benjamin, Mondrian '63-'96, 1987, video, transferred to DVD, 25 minutes, English with Serbo-Croatian subtitles (© Museum of American Art)

|

Elsewhere at HMKV, housed in the great hall of the spare-parts

warehouse of the disused neighboring factory, Walter Benjamin,

resurrected in 1987, lectures on the value of Mondrian copies, arguing

that they are more complex than the originals. This Benjamin's

compatriots, Slovenian art and music project Laibach, have long been

proponents of the "Monumental Retro-Avantgarde," whose founding

manifesto states: "We proclaim that copies have never existed and we

recommend painting from pictures painted before our times. We claim

that art cannot be judged from the viewpoint of time. We acknowledge

the usefulness of all styles for the expression of our art, those past

as well as present."14 This

insistence on "usefulness" seems to resonate with the notion of

"effective history" that Foucault borrows from Nietzsche. In his book

about Laibach and the NSK collective, Alexei Monroe sees in this

retrogardism an opportunity to "unfreeze" the situation, "enabling

disruption, change and reformation. Yet," he continues, "this is not an

avant gardist attempt to construct a new future based on negation of

the past. Rather, retrogardism attempts to free the present and change

the future via the reworking of past utopianisms and historical wounds."15 This idea is perhaps most cruelly demonstrated in Artur Zmijewski's 80064, 2004, in which

an Auschwitz survivor is persuaded to have his tattoo refreshed, the present literally overwriting the past.

It is this emphasis on the present that differentiates much of the work included in History Will Repeat Itself

from other forms of bringing history to life. Whereas historical

dramatization tries to visualize the unknown and unknowable, imagining

the detail of unfilmed battles or putting words in the mouths of famous

leaders to produce biographies and historical epics, artistic

re-enactments often limit themselves to the known, however partial,

filling in the gaps to produce a genealogy of current conditions. To an

extent, these re-enactments are preoccupied with a question of scale.

Earlier this year, at the Materialism Today conference at Birkbeck University, Slavoj

Zizek posited the ontological incompleteness of reality, which, like

the unrendered interior of an unexplored house in the background of a

videogame, is not determined to a point beyond the atom. Magnifying the

past beyond the point we know to be determined by historical

documentation, we arrive at a similar cul-de-sac where we quickly have

to fill in the pixels. This may point to a radical shift in our

perception of history in the digital age. If the most significant sites

of recent history have operated thus far as invisible black holes (from

Nazi death camps to Tiananmen Square and Guantánamo Bay), we

increasingly assume that the past is subject to total access. A

reconfiguration of the search parameters or a digital zoom at a higher

resolution are all it takes not to get to the truth of an event, but to

actually participate in historical events such as the recent open call

for a Google Earth search after lost pilot Steve Fossett.

|

|

|

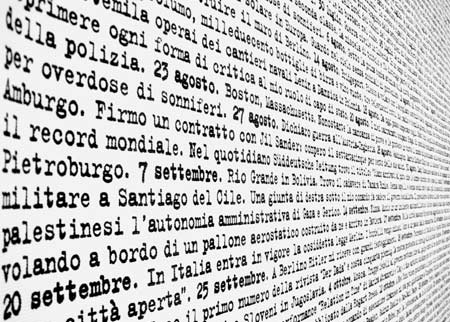

top:Daniela Comani, Ich war's. Tagebuch 1900-1999, 2005, book project for Revolver-Archiv für aktuelle Kunst (courtesy of the artist);

bottom:

Daniela Comani, Ich war's. Tagebuch 1900-1999, 2006, installation, digital print on net vinyl, 300 _ 600 cm (courtesy of the artist)

|

As artists appropriate more moments for themselves, they will not be

reclaiming them from the media as such, but rather producing their own

private mediatizations, turning them into individual experiences for

their viewers. This shift will require us to move away from an

understanding of repetition as technical reproduction, for the

repetition of an act, unlike the reproduction of an object, does not

diminish its cult value, as the real Walter Benjamin wrote in 1936.

Instead, this repetition turns event into private ritual, an idea born

out by Tom McCarthy's pivotal novel of re-enactment, Remainder, included in part in the catalogue of

History Will Repeat Itself, in which, following an accident, the

protagonist finds himself compelled to repeat increasingly violent

events with the aid of paid actors and staff-the repetition heightening

his sense of an otherwise dim presence in the here and now. Like

Zmijewsky's film, McCarthy highlights the potential for sadism within

the framework of the re-enactment and the power relations produced in

taking ownership of history. In Daniela Comani's installation, Ich War's. Tagebuch 1900-1999,

2006, the artist reports her presence in the first person at every

significant event of the twentieth century, becoming history. Writing

about the relationship performance produces to the past, Joseph Roach

has employed the metaphor of a necrophilic impulse, seeking "to

preserve a sense of the relationship to the past by making physical

contact with the dead."16 In exhuming these raw

data corpses, reordering and staging them as actors in new old plays,

contemporary art is writing its own genealogy, in which private,

individualized, unofficial versions compete for cultural space in the

public sphere.

|

|

|

Daniela Comani, Ich war's. Tagebuch 1900-1999, 2006, installation, digital print on net vinyl, 300 _ 600 cm (courtesy of the artist)

|

NOTES

1. Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, Donald Nicholson-Smith, tr., New York: Zone Books, 1995, originally published in French in 1967.

2. Peggy Phelan, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance, London: Routledge, 1993, 146.

3. Rebecca Schneider, "Solo Solo Solo," in After Criticism: New Responses to Art and Performance, Gavin Butt, ed., Oxford: Blackwell, 2005, 33.

4. Philip Auslander, "Liveness," in Performance and Cultural Politics, Elin Diamond, ed., London: Routledge, 1996, 198.

5. Mark Cameron Boyd, "Performance Simulacra: Reenactment as (Re)Authoring," Theory Now, 2007, at: http://www.theorynow.blogspot.com/2007/05/performance-simulacra-reenactment-as.html, accessed September 30, 2007.

6. Melanie Gilligan, "The Beggar's Pantomime: Performance and its Appropriations", Artforum, Summer 2007, 429.

7. Lütticken, Sven, "Planet Of The Remakes", New Left Review 25, January-February 2004, 119.

8. Iain Forsyth + Jane Pollard, all quotes from conversation with the authors, September 2007.

9. Inke Arns, all quotes from conversation with the authors, September 2007.

10. Jacques Rancière, "The Emancipated Spectator," Artforum, March 2007, 274.

11. Michel Foucault, "Nietzsche, Genealogy, History," in: Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews, Donald F. Bouchard and Sherry Simon, tr., Oxford: Blackwell, 1977, 143.

12. Ibid., 154-5.

13. Rod Dickinson, email to the authors, September 2007.

14. Alexei Monroe, Interrogation Machine: Laibach and NSK, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005, 53.

15. Ibid., 120.

16. Joseph Roach, "History, Memory, Necrophilia", in The Ends of Performance, Peggy Phelan and Jill Lane, eds., New York: New York University Press, 1998, 29.

Contributing

Editors Pil and Galia Kollectiv are London-based artists, writers, and

independent curators. Their essay "Militant Ironies: Art as a Strategic

Weapon in Israel's Culture Wars" was published in ART PAPERS 30:05

(September-October 2005).

|

![]()

![]()